By Sandhya Sridhar

India is a country of festivals. And festival time makes one retrospect, when memories of the shared festivals of the years gone by keep the links alive. But outside the festival time, who are we? Do we continue to retain our Indic nature at its truest?

Everyone speaks of the argumentative Indian. There is also a book by that name. For you and me, it was the socially-invested, ‘I know everyone and everything that happens in my vicinity’ kind of chap. He or she was the person who when you found them next to you on the train, took the duration of the journey to understand who you are, where you came from, what you do and how much you earn, not to mention the details of your family matters. You are being an argumentative Indian as well, gave into the mood of the moment and in turn, got details of your new friend’s life and matters. In that journey, it seemed to you that you had a friend for life.

You discussed society, politics, differed and agreed on matters of faith and belief and many other things. It was a deep dive into each other’s lives that has no other parallel. You parted, with the understanding that this was the end, and thought no more about it, perhaps mentioning this travel partner in some conversation where his opinion or life story was relevant.

However, what was not said at all, is that this argumentative nature, was also a tolerant one. The tolerant Indian accepted the person who was sitting next to him or her. It did not matter who he or she was, what kind of a background he or she hailed from, not to mention religion. It was a complete joy to share those differences, to hear their own stories as they saw them, and discuss the intricacies of those differences. There could have been judgement, and if there was, the argumentative side surfaced. If there was none, then the tolerance held good.

The Gujarati garba

This has been the psyche of our country for decades. Trains, buses and public places were spots of interaction and discussion. The telephone once, was not so ubiquitous, so people enjoyed the company of the other with less complexity. It could be that sometimes, there would be disagreement and some amount of acrimony. But then, there were always people around you to help you settle it and part without engaging further.

However, look at the train or the bus today. Very few really want to engage with their neighbour. Everyone has a mobile phone in hand. Everyone has tunnel vision, and the algorithms of the electronic world show you the mirror of your mind. There is no real engagement except when you want to use the loo and you say, “Excuse me, let me pass.” Or you pass the food tray to the person sitting by the window.

Besides, the gloves are off. There is more rage in the air. More anger. And more intolerance. It does not take a little more than a wrong word to trigger the action. So there is some fear in engaging with whoever is next to you. You would rather smile or ignore, than engage and discuss.

Yet, there is the rare occasion when someone does hold out a home-made sweet and then, the innate Indianness accepts it with grace, and the engagement takes place. You put away the phone and actually talk.

It was that once, a village raised the child. Everyone knew everyone else, and if you stole your neighbour’s chicken, the whole village knew, however much you tried to hide the boiling pot of chicken curry. You met everyone on your way to work and back. There would be exchange of news and you had time. Community life was cherished, with its good and bad aspects.

The South Indian golu, or festival of dolls

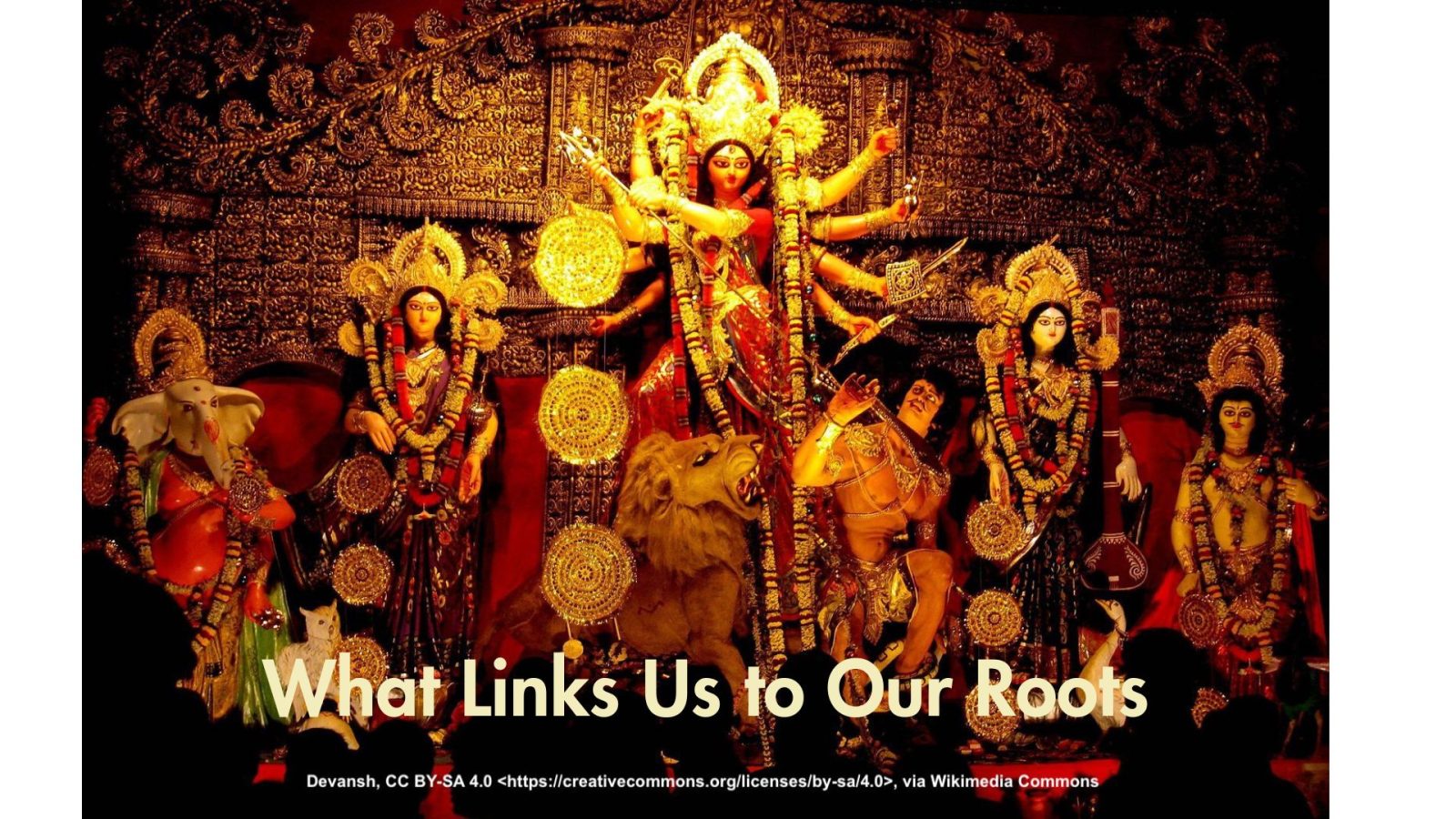

Today, despite all life’s pressures, people do try to hold on to that community life in festival time. The Navarathri is one such. In the varied regions of the country, are rituals and practices that involve the community. This is one festival in which people reach out to one another in some way or the other, as the community dance, home visits for kolu or at the Durga puja pandals. These practices help us refresh bonds, interact in shared happiness and keep the human spirit positive.

Our cultural roots survive in our continued practice of the festival rituals. It is important to keep them alive.

Leave a Reply