By Sandhya Sridhar

Much has been written about M.K. Gandhi’s experiments with truth and his vow of Brahmacharya. Much has also been written about the various women in his life, many of them his bed-mates in his quest to master his celibacy, a process which he called ‘yagna’ or his quest for truth.

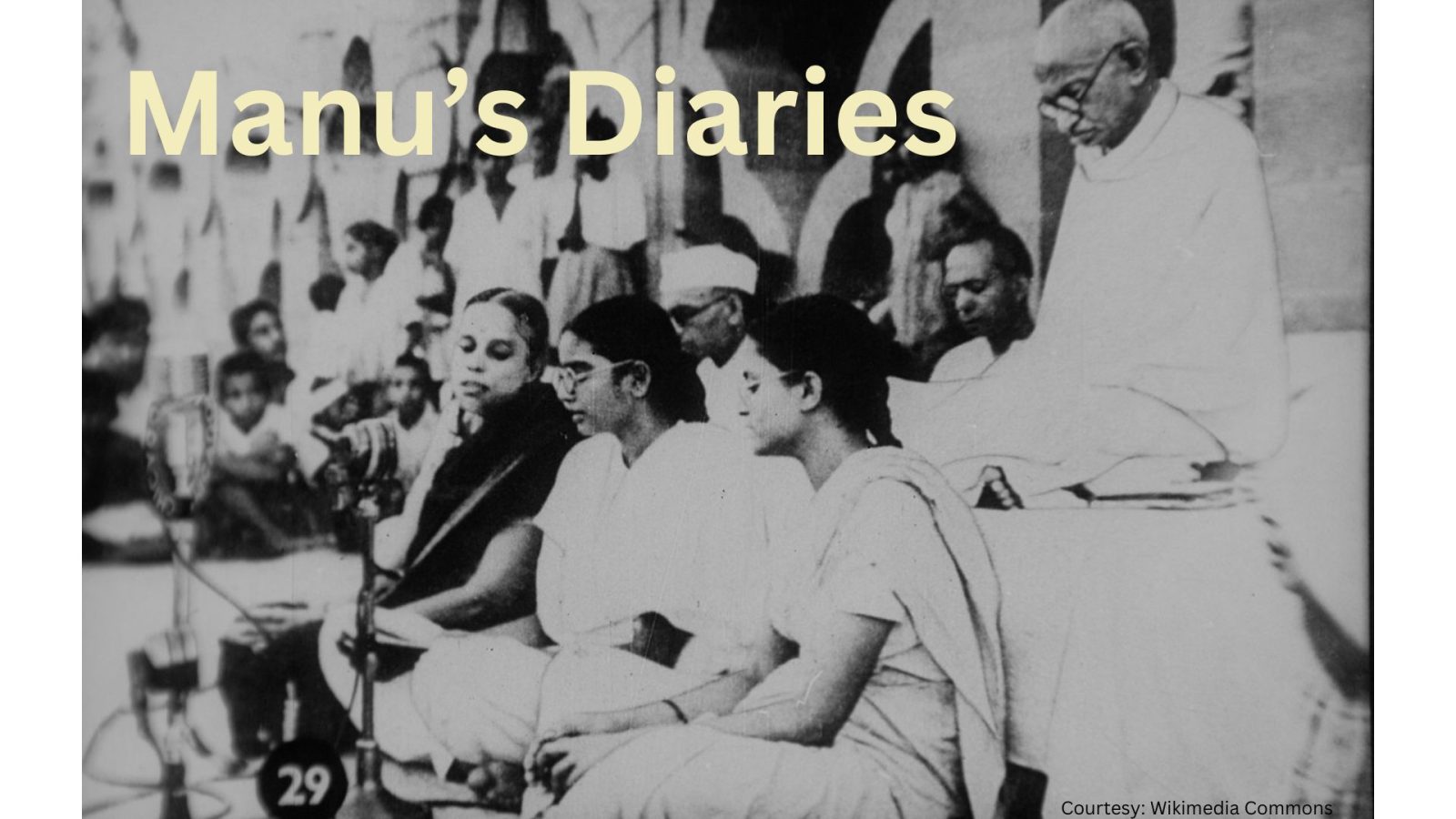

Manu Gandhi, whose full name was Mridula, was the daughter of Gandhi’s nephew Jaisukhlal, who joined his ashram, Sevagram, when she was just fourteen. Gandhi encouraged Manu to keep a diary. When the Quit India Movement was launched, Gandhi along with his wife Kasturba, and many of his associates, were arrested and interned at the Agha Khan Palace in Poona. The women of the ashram including Manu, also decided to join the protest and soon enough, she was sent to the Aga Khan Palace with the others. Her diary reveals the details of her everyday life there, and we see that her duties included ‘squeezing’ juice for ‘Bapuji’, cooking and cleaning. She was mostly a caregiver for Kasturba, taking care of her health, darning her clothes, making her bed.

In between all these chores, Manu learns grammar and English, reads the Gita or the Ramayana, and takes lessons in history from Pyarelal, Gandhi’s secretary, or geometry from Gandhi himself.

Manu’s diaries between 1943-44 have been translated from the original Gujarati and published by Oxford University Press. This offers us a close view of how life in proximity to Gandhi and Kasturba must have been for the young girl.

Her entries show the innocent young girl earnestly documenting her daily routine, and showing them to Bapuji, who corrects her entries. She notes the day when Sushilaben’s hair was cut, noting how the latter had a smile on her face while it was being done. Manu notes that thirteen girls have had their hair cut by Gandhi.

Manu plays ping pong and badminton, and describes celebrations on festive days. Then there is also an instance of a misunderstanding with Sushilaben who teases her for vomiting, which Manu takes to heart and cries.

The days are filled with instances like these, letters received, food that is cooked, headaches, ailments, and of sweets being made for Gandhi’s birthday, the celebrations that follow.

Manu, as it has been documented, was by Gandhi’s side on the fateful day when Nathuram Godse fired those shots that killed him. Manu was also part of Gandhi’s experiments on celibacy, and was one of the women who slept in his bed as part of this exercise.

Manu, however, wrote that Gandhi was like a ‘mother’ to her, giving her the love, affection and care that a mother would.

Gandhi’s renunciation into Brahmacharya, is a complicated discussion. It takes with it much of Hindu thought and Western philosophy, and he admits in his autobiography that he had not spoken to his wife Kasturba about it, until it was time to take the vow. Kasturba, as was her wont, was supportive.

He writes, “…I had great difficulty in making the final resolve; I had not the necessary strength. How was I to control my passions? The elimination of carnal relationship with one’s wife seemed then a strange thing.”

But Gandhi took this further, testing his Brahmacharya constantly, invoking it as he shared his bed with many of his close women associates. There was disapproval from many, with some of the ashramites telling him that his walking with his hands on the shoulders of women, was not acceptable. This was all the more so, for while Gandhi himself had women sharing his bed, husbands and wives who lived in the ashram were told to practise celibacy and stay apart.

Many were the women with whom he practised ‘losing his sexual consciousness’. Manu was one, so was Abha, another niece, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Dr. Sushila Nayar (Pyarelal’s sister) and Miraben.

Manu’s diaries are invaluable for her notations and observations, which chronicle her daily life by Gandhi and Kasturba’s side.

When Manu entered Sevagram and was arrested and interned at the Agha Khan Palace, she was all of fourteen. When Gandhi was assassinated, she must have been about nineteen years old. She was forty years old when she died a spinster, in Delhi.

Manu, in a sense, was an enigma, a woman whose identity hung on the man who was perhaps the most well-known of his time in the sub-continent. Her diary entries show a girl who aligns herself unquestioningly to ‘Bapu’ and ‘Ba’ – her bouts of rebellion, anger or hurt mere flashes, and are insights into how relationships at the ashram were wired.

Who was Manu within? Was her life after Gandhi, empty or did she find new purpose? We may never know.

Leave a Reply